Preventable Diseases, Preventable Tragedies: Why Vaccines Are Essential

Vaccines save lives but only if people use them!

Today is the British Society for Immunology’s Vaccination Engagement Day which seems a fitting day to reflect on the success of vaccines but also the challenges for vaccine uptake and understanding. This article is a shortened version of the latest Independent SAGE report also out today on vaccines and preventable infections. The report was written in response to the unprecedented drop in vaccine uptake and the proliferation of mis- and dis-information on-line and in the main press.

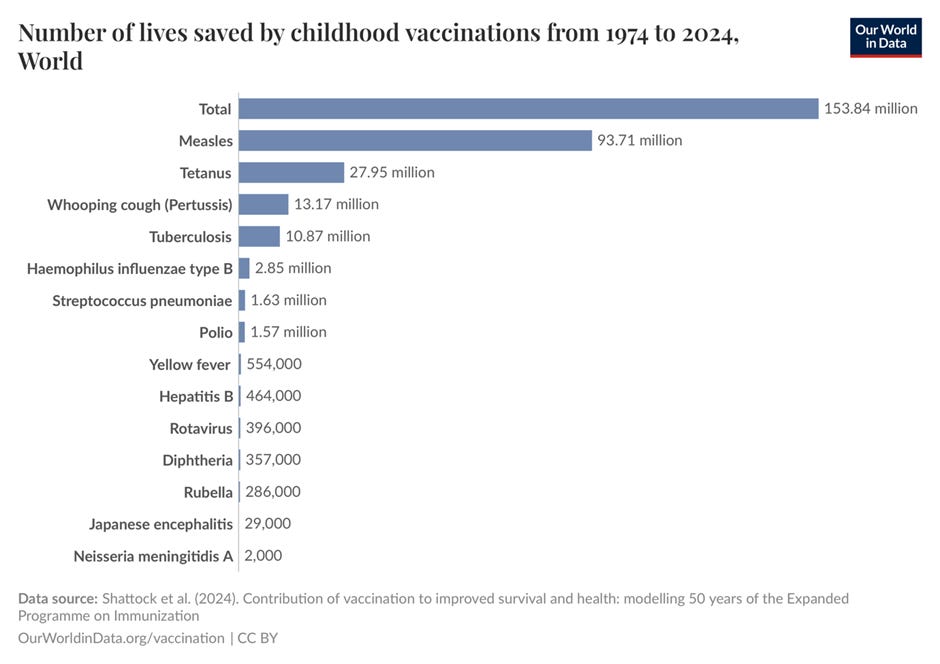

Vaccines have transformed health expectancy and health outcomes.

Vaccines have been an incredible success: from the earliest vaccines developed by pioneers including Edward Jenner for small pox in 1796 and Louis Pasteur for rabies in 1885. Most recently, innovations in vaccine technology by Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman lead to the development implementation of mRNA vaccines that underpinned the development of vaccines targeting Covid-19 and even some cancers. Thanks to vaccination, elimination, meaning no sustained community transmission of a pathogen, has been achieved for multiple infections in the USA, UK and other countries. However, vaccination has also become a victim of its own success. Diseases such as whooping cough and measles that were once common killers in the early 20th centuries are now so much rarer that most people—including many clinicians—have never seen a case. Mis- and dis-information about adverse effects of vaccines, whether true or false, are now also ubiquitously amplified on social media.

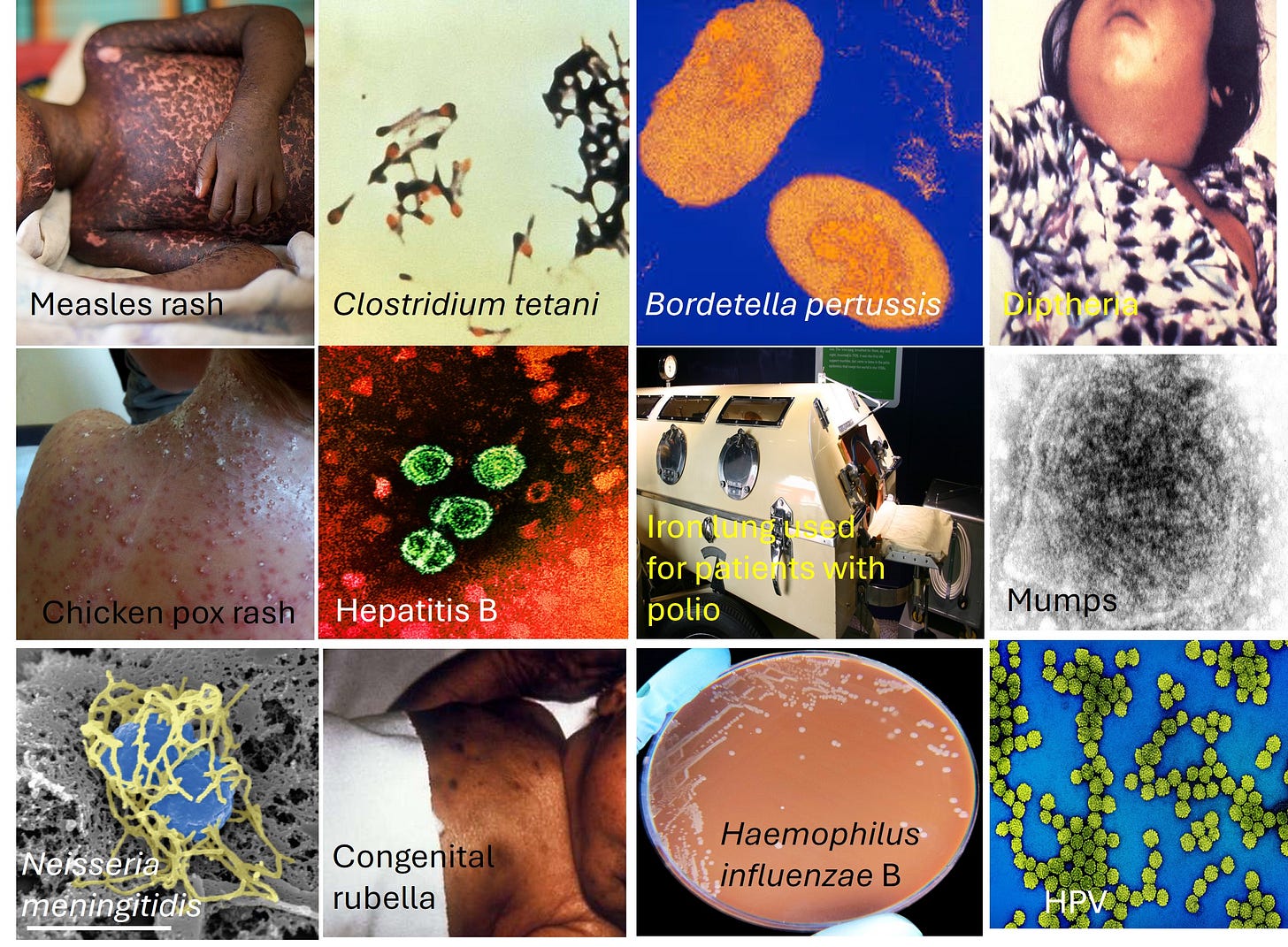

Childhood immunisation rates have been falling for several years with the WHO estimating that 3 in 4 infants live in countries or counties where low vaccine coverage is driving measles outbreaks. This is perhaps epitomised by the growing numbers of cases and states affected with measles in the USA. The report by Independent SAGE discusses some once common diseases that can or have been controlled by vaccines including Measles, Tetanus, Whooping Cough, Diphtheria, Chickenpox, Hepatitis B, Polio, Mumps, Meningococcal Disease, Rubella (German Measles), Haemophilus Influenza B (Hib), and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV).

Images of vaccine preventable infections or the symptoms they can cause. All images Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

What is vaccination and how does it work?

Individual immunity

When we get infected with a pathogen our white blood cells- immune cells- quickly detect and try to deal with the threat. However, if this the first infection with that pathogen, it takes a little time for the body to generate the specific white blood cells and antibodies that are tailored for that pathogen. This lag creates a window of opportunity for the pathogen take advantage which can making you very sick or can even be fatal. Once our immune cells have learned about a specific pathogen they have “memory” of that meaning they can respond much more quickly should you encounter the pathogen again. A second infection may not occur at all or may be milder than the first.

A vaccine helps develop immune memory without having to risk the infection which is a LOT safer. Vaccines are usually a safe weakened (‘attenuated’) or killed form of a specific pathogen, or part(s) of the pathogen in isolation that can be delivered using a variety of vaccine types. Some vaccines require several doses initially to ensure you get the best possible immune response- an example is the MMR vaccine and the protection it confers is not optimal unless the full course of vaccines is taken. Some vaccines for diseases such as flu, require annual boosters due to a combination of changes in the virus structure and waning immunity.

Vaccine campaigns are often targeted to the most vulnerable people such as young babies and the elderly who are most at risk of severe infection. Some vaccines will make you immune to ever contracting the infection- this is known as “sterilising immunity” whereas others (such as COVID) still partially prevent infection and dramatically reduce the chances of severe illness or death.

Population immunity

As well as protecting the individual, vaccines benefit the community. The more people that are vaccinated, the better because that means fewer people are likely to become infection hosts and “Typhoid Mary’s” spreading the infection to others. If more people are vaccinated the pathogen has nowhere to go and its numbers will start to decline also known as “population immunity”. Population immunity has been transformational in reducing many formerly common diseases to very low levels in many countries (e.g. polio or measles).

The name “Typhoid Mary” refers to a cook who is believed to have unintentionally infected between 50-122 people with typhoid fever. She was an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogenic bacterium Salmonella typhi. The term is now a colloquial term for anyone who spreads disease or something else undesirable. Image used using Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

How a disease spreads is determined by both how infectious it is, as well as how many people in the population are susceptible to infection. A person who has never met the pathogen is susceptible whereas someone who has had the disease or been vaccinated will often be immune. For a disease to spread, each infected person must, on average, give the disease to more than one other susceptible person. But if an infected person passes the pathogen to fewer than one other person on average, then the number of infections in the population starts to fall. This “basic reproduction number”, or “R0”, is an estimate of how many people, on average, an infected person passes the pathogen to. The higher the R0, the higher the percentage of the population will need to be vaccinated to prevent an outbreak spreading. Measles has a high R0 - around 18- so 92-95% of the population must be protected to prevent (or curtail) an outbreak. Historically, this level of population immunity has only ever been achieved through concerted vaccination programmes. If fewer people take up the vaccines on offer though, the pathogens can exploit this gap in population immunity resulting in abrupt rises in cases. For example at least 378 cases have been reported in 17 states of the USA typically in un- or under-vaccinated children and two unvaccinated individuals have tragically died.

Why is vaccine uptake falling?

One reason for the reduction in vaccine uptake is the rise in vaccine hesitancy which has led the WHO to declare it as one of the ten biggest risks to human health. Vaccine hesitancy refers to a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. However, vaccine hesitancy does not fully account for the reduction in vaccine uptake with a combination of factors influencing the likelihood vaccines uptake including how accessible vaccines or information about vaccines is, prior negative health-care experiences and mistrust of organisations or advocacy of alternative healthcare all being factors.

The ‘5 Cs’—Confidence, Complacency, Convenience, Communication and Context ar often used to explain reduced vaccine uptake. ‘Confidence’ considers fears around the safety and efficacy of vaccination and the possibility of side effects versus the risk of the actual diseases. Like any medicine, vaccines can have very rare side effects which is discussed more fully in this report. Confidence is also linked with ‘Complacency’ about the severity of eliminated or seasonal diseases has become more common as fewer people have experience of these diseases. Misunderstanding of the risks of a disease versus the risk of being vaccinated against that disease plays into this. Complacency is also linked to ‘Convenience.’ Vaccines may not be easy to access- for example appointments are in work hours, or vaccine centres are far away and inaccessible by public transport or their be a fee for the vaccine- all of which can dissuade people from being vaccinated. This factor likely impacts those from more socio-economically deprived backgrounds further compounding pre-existing health inequalities.

‘Communication’ about vaccines is critical - how accessible and clear the information is regarding vaccines, including where and when it is available locally. Good communication can have a positive influence on confidence. Barriers to communication are evidenced by the recent announcement by the Louisiana surgeon general for its staff to stop engaging in media campaigns and encouraging vaccines even though vaccines will still be available. ‘Context’ is also important- considering cultural sensitivities and needs—for example, informing people if vaccines are halal or suitable for vegans.

Misinformation (that is, information that is incorrect, whether intentional or not) and disinformation (information deliberately put out to mislead), especially on social media, add to vaccine hesitancy by sowing confusion and fuelling uncertainty and breed vaccine hesitancy. For example, an alleged link between the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism spectrum disorder has been widely circulated despite this alleged link been thoroughly debunked in multiple studies. For example, recent statements by the US secretary for health RFK Jr, who has a history of spreading vaccine disinformation, have cast doubts on the severity of measles and the risks of vaccination.

Vaccines should be celebrated as a global success story

Despite the success of vaccines, we are facing a crisis of public confidence in the efficacy and safety of vaccines. Vaccines have transformed our life expectancy so that fewer people should have to face the horrors of seeing a loved one suffer or even die of diseases such as measles. The author Roald Dahl, who watched his daughter Olivia tragically die of measles, said:

“I should think there would be more chance of your child choking to death on a chocolate bar than of becoming seriously ill from a measles immunization. So what on earth are you worrying about? It really is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunized”

I hope you will find our report from Independent SAGE helpful and do also look to trusted organisations such as The British Society for Immunology who published this pamphlet tackling common questions about childhood vaccines.